Drury students study space debris with veteran NASA professor

Campus News October 6, 2017, Comments OffArticle by Johan Englen

Two large metal objects, while in orbit, collide into one another at breakneck speeds over Earth; this collision creating a massive explosion with thousands of shrapnel-pieces shooting off in many directions.

This isn’t a Michael Bay movie scene. This is real life. At least it will be… in a couple of decades. Space debris, like the shrapnel in the scenario above, is a growing problem in the world of space travel and astrophysics. Most objects, or at least pieces of those objects, that humans have shot into space come directly into orbit with Earth – potentially causing issues in the relatively-near future.

“The parts of space shuttles that you see break away from spaceships, they don’t go away. They stay up there and we’ve launched a lot of things up there. There are decommissioned satellites and old parts of space shuttles. Eventually it will become a problem,” said Jaxon Adams, a freshman physics student.

Drury students, being led by a faculty member, are preparing a special physics research project to study the rotation of space debris in orbit with Earth to better understand this looming problem in space travel. Adams is one of around eight students working on the project. Students don’t get a grade on it, though. It is simply a side project that interested students can use to satisfy their intellectual curiosity and put on their resumes.

Adams sees the project as a good stepping stone toward a possible career as an astrophysicist, hopefully with NASA. More than that though, he is amazed at the thought of it.

“I just think the idea is so cool. I mean. the idea that us mere mortals could know about something that’s going around 1,000 miles above our head just by some calculations and printing a little 3D model. It’s crazy,” said Adams.

Greg Ojakangas, project leader and associate professor of physics at Drury, explained the three parts of the project. Ojakangas has a massive amount of experience in this area due to his work with NASA. He used to work full-time on this issue and was a consultant until “a few years ago.” Due to the funding drying up, he’s now doing this project with the students.

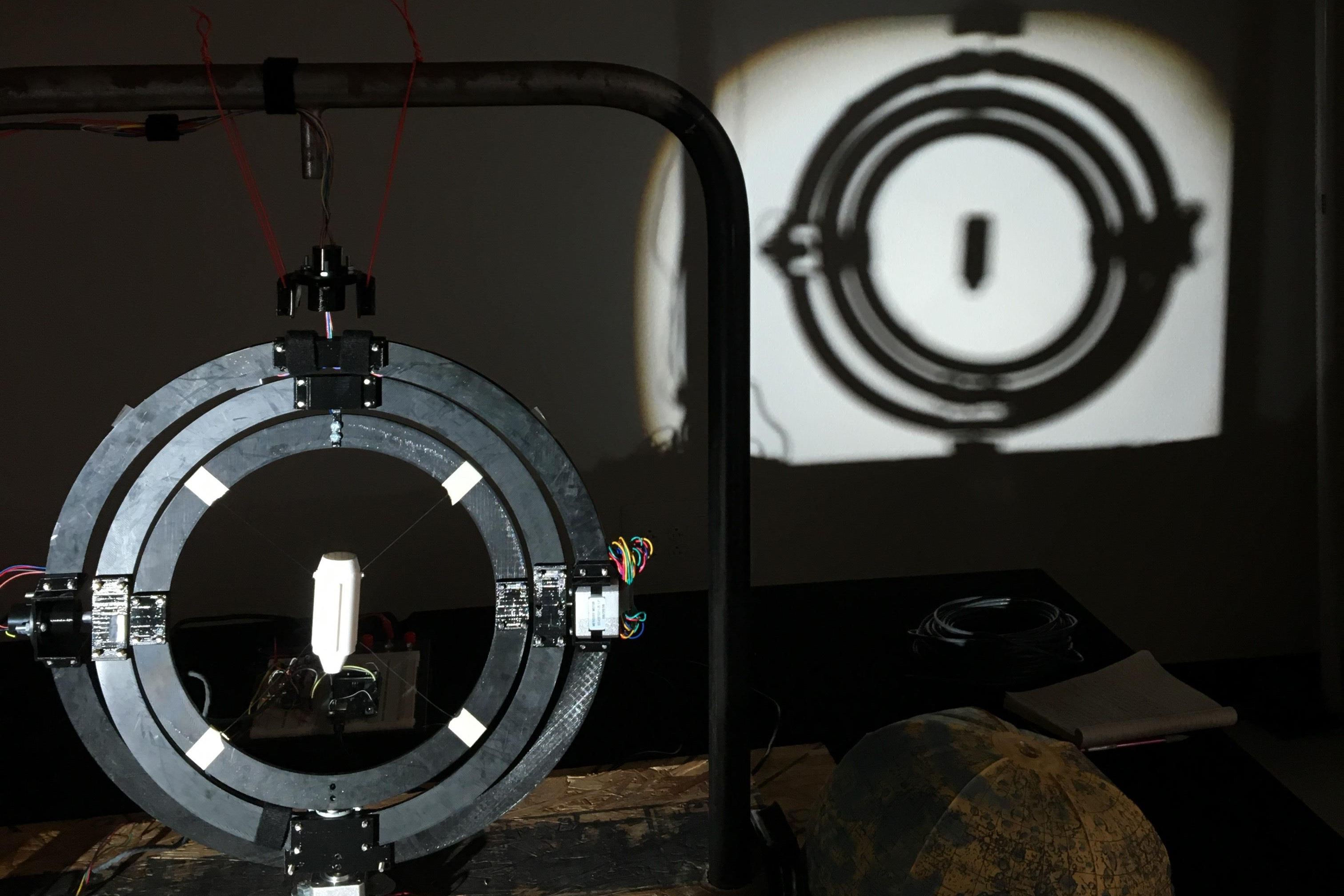

First, they will simulate the theoretical spin of certain debris that they know are orbiting Earth. Using a gimbal system, a pivoted support that allows the rotation of an object about a single axis, the team will rotate a suspended 3D-printed model of space debris in three axes, while shining a simulation of the Sun at different angles. Second, they will use computer programs to also simulate the rotations. Lastly, they will actually observe and take real data at Ojakangas’ own observatory of some debris that will be passing over Springfield in the near future.

“NASA is interested in understanding how [debris] is rotating because these objects are about the size of a school bus. When they hit other debris, they break into thousands of pieces and they’re all moving tens of thousands of miles an hour. It is like an explosive and it is basically a runaway chain reaction. The problem is getting worse; it has been for a long time,” said Ojakangas.